![]()

While museums struggle lamely to incorporate the Internet

in their exhibits, a tight community of digital artists has long been

flourishing on the Web. In the current ArtForum, Rachel

Greene, co-founder of Rhizome, reviews the history of Internet art: "The

term 'net.art' is less a coinage than an accident, the result of a

software glitch that occurred when Slovenian artist Vuk Cosic opened an

anonymous e-mail only to find it had been mangled in transmission. Amid a

morass of alphanumeric gibberish, Cosic could make out just one legible

term -- 'net.art' -- which he began using to talk about online art.

Spreading like a virus among Internet communities, the term stood for

communications and graphics, e-mail, texts and images; it was artists,

enthusiasts, and technoculture critics trading ideas, sustaining one

another's interest through ongoing dialogue." ![]()

The Whitney also gestured towards the Net in its Biennial this year, and, in keeping with its Upper East Side address, its approach was to simply (and finally) include Net art, demonstrating both its hipness and its power to bestow a certain legitimacy upon any new medium. Unfortunately, despite much fanfare and a party thrown by Rhizome (a site dedicated to new media art), the result was not unlike witnessing the Hottentot Venus sitting miserably in her cage. There is hardly a consensus on the best way to exhibit Net art, but it's generally understood that it should be an interactive experience. In the Whitney's Internet art gallery, viewers were expected to sit and watch the selected sites, which were projected onto a large screen at the front of a small room. Anyone was allowed to control what everyone else saw, using a computer located in the back corner. This was a weird inversion of the democratizing power usually ascribed to the Web; here you are subjected to whims ranging from bold to sadistic.

On a recent visit, I witnessed two teenage boys taking advantage of the crowd. After scrolling down Mark Amerika's ancient Grammatron for a few minutes, one of the boys abandoned his seat to leave visitors watching motionless text. As they left the room, the other boy turned to his mouse-wielding friend and laughed. "That was so funny," he said. "Why?" his buddy asked. "Because people thought that they were watching something," answered the first kid. "But they were just watching you click and click."

To be fair, there is a small bank of computers situated

on the lower level so that visitors can browse through the sites on their

own. It's a diverse selection. Darcy Steinke's Blindspot is suspenseful and well designed; a sort of

"choose your own adventure" involving a mother alone at home late at night

with her child, struggling to avoid her paranoid fantasies. Fakeshop, which

automatically displays a series of windows with text and images, actually

looks fairly splendid blown up on a big screen. Its neurotic messages

popping up in "script alerts" saying stuff like "Protect your online body

from improper touching" are doubly potent when they appear larger than

life. In the end, though, the Whitney's attempt to carve out stars from

the vast Net art community seems quaint; when the Web sites aren't clunky

and obsolete (such as Grammatron, which, though it seems excruciatingly

boring to me, does deserve some credit for establishing the Net as a

platform for art) they are the product of a collaborative effort. Rtmark, a collective of

anticorporate activists, locates itself more in a political world than an

artistic one. The group created a new address for the Whitney's show and

"donated" the space to whoever submitted their site to them (although an

explanation from Rtmark, remains on the screen). A continual rotation of

sites unrelated to Rtmark both amateurish and sophisticated, are on view.

To be fair, there is a small bank of computers situated

on the lower level so that visitors can browse through the sites on their

own. It's a diverse selection. Darcy Steinke's Blindspot is suspenseful and well designed; a sort of

"choose your own adventure" involving a mother alone at home late at night

with her child, struggling to avoid her paranoid fantasies. Fakeshop, which

automatically displays a series of windows with text and images, actually

looks fairly splendid blown up on a big screen. Its neurotic messages

popping up in "script alerts" saying stuff like "Protect your online body

from improper touching" are doubly potent when they appear larger than

life. In the end, though, the Whitney's attempt to carve out stars from

the vast Net art community seems quaint; when the Web sites aren't clunky

and obsolete (such as Grammatron, which, though it seems excruciatingly

boring to me, does deserve some credit for establishing the Net as a

platform for art) they are the product of a collaborative effort. Rtmark, a collective of

anticorporate activists, locates itself more in a political world than an

artistic one. The group created a new address for the Whitney's show and

"donated" the space to whoever submitted their site to them (although an

explanation from Rtmark, remains on the screen). A continual rotation of

sites unrelated to Rtmark both amateurish and sophisticated, are on view.

WHILE THE WHITNEY took up the challenge of exhibiting Net art (with only modest success), P.S. 1 accepted the Net at face value as a tool for communication. Many artists were excited by the prospect of hearing directly from their audience. Since only a minority of artists incorporated any sort of technology into their pieces, the relationship of each to their e-mail account was fairly straightforward.

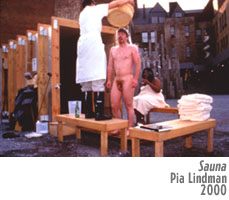

An art teacher in Canada sent Pia Lindmann, a Finnish

artist who built a sauna in the courtyard, a flattering critique. He then

followed up with a list of questions about her work, formulated by his

high-school class, which she duly answered. Adriana Arenas, a Colombian

artist, received what she felt was a particularly insightful e-mail from a

girl attending an elementary school in Westchester. Arenas's stunning

video installation includes a split screen showing pink cotton candy being

made while saccharine Spanish love songs play in the background -- the

translation appears in script on a television in front of the

confectionery images. After choosing Arenas's piece as her favorite, the

girl writes that she "enjoyed the way the cotton candy actually moved with

the music." This might not constitute nuanced dialogue, but Arenas is

content. "She really got it," she says happily.

An art teacher in Canada sent Pia Lindmann, a Finnish

artist who built a sauna in the courtyard, a flattering critique. He then

followed up with a list of questions about her work, formulated by his

high-school class, which she duly answered. Adriana Arenas, a Colombian

artist, received what she felt was a particularly insightful e-mail from a

girl attending an elementary school in Westchester. Arenas's stunning

video installation includes a split screen showing pink cotton candy being

made while saccharine Spanish love songs play in the background -- the

translation appears in script on a television in front of the

confectionery images. After choosing Arenas's piece as her favorite, the

girl writes that she "enjoyed the way the cotton candy actually moved with

the music." This might not constitute nuanced dialogue, but Arenas is

content. "She really got it," she says happily.

The effects of having a P.S. 1 e-mail account played out a bit differently in the hands of Kevin and Jennifer McCoy. Their multimedia artwork, Radio Frankenstein, transmits a radio signal with excerpts from Frankenstein read by digital voices to small handheld radios. The McCoy's art, which is also Web, often deals with networks. They seem like perfect candidates for the e-mail project. According to Jennifer, "We don't just make objects, we're really interested in systems. This kind of systemic discussion is moving in and out of the artwork in a really kind of seamless way."

But systems beg to be split open, explored, then redefined. Huberman exploited the free services available on the Web, using Hotmail to create the artists's accounts. (Every address followed the same format: lastname_greaterny@hotmail.com.) In a coup that similarly proved the elasticity of the e-mail project, the McCoys set up a Greater New York account for Cary Peppermint, a conceptual artist whose work was not included in the show, after reading a weepy letter he'd posted on Rhizome's listserv addressed to the curators of Greater New York. "It is with much regret, I realize we must have somehow missed each other during your curatorial undertakings for the creation of this show," Peppermint lamented. "I would like to further contribute toward the diversity of ideas and creative practices found in the metropolitan area by presenting you with USE CARY PEPPERMINT AS MEDIUM: EXPOSURE #8818: AN ART AUCTION VIA EBAY.COM."

Kevin McCoy responded to the letter: "Dear Cary, as an artist officially sanctioned to be included in the show 'Greater New York' at P.S. 1, I have authorized you to receive the same benefits and privileges extended to the other artists in the show, namely, your own official 'Greater New York' Hotmail account." Rhizome provided a venue for the exchange to take place and P.S. 1 inadvertently supplied the tools to give Peppermint a presence in the exhibition, albeit one no one would see.

"There's some Jasper Johns and Rauschenberg story," Kevin recalls later, "in the sixties, where one guy got in the show and the other one didn't, so the one guy showed the other guy's stuff." Jennifer agrees, "It was just sort of a cultural moment, and we just let it lie there."

AS IT TURNS OUT, it was Lindmann, whose work is rooted in sensuality and physical space, who received the largest amount of e-mails. An officious attendant at her sauna, Lindemann dumps cold water on naked participants and encourages them to sign the guestbook. She wants Americans to feel more comfortable in their own skin. She was thrilled to correspond with viewers in such an intimate format, and moved her Greater New York e-mails to her personal account after receiving them. Many of the e-mails other artists received were chatty and informal, typically asking questions and complimenting the piece. But those who contacted Lindmann treated her like their confessor. One man wrote to tell her that her work changed his life: Before the sauna, he'd been unbearably insecure about his body. "He would not have written that into the guestbook," Lindmann insists. "Sending it out into the dark world and knowing that no one's going to catch it but me -- I think that makes it easier."

Many artists seemed to disagree that the Net opened up channels for audiences to reach them that hadn't previously existed. One suggested that a pay phone would have served the same purpose. "People have always been available," said another. "It's just a perception that the art object is this really strong thing that is unassailable or irreducible or undiscussable. It's kind of problematic."

Yet whether it's spontaneous or carefully composed, communicating with a stranger is far more comfortable when mediated through e-mail, which provides a necessary, if illusory, distance. Most people feel out of their depth discussing contemporary art, and the elliptical nature of e-mail offers an informal yet intimate space for asking questions, not to mention the simple logistical fact that it's impossible to imagine artists willingly posting their phone numbers on their nameplates. E-mail permits them to respond at their own convenience. Amidst the hand-wringing (and studies) about the Internet encouraging antisocial behavior, it's worth contemplating that in many ways it's easier than ever to contact people we tend to elevate; a little hunting might yield the address of an admired author, for example. "Just being able to see that the artists are available to you, that if you do want to try to enter into their microcosm they're there for you -- that's enough," Huberman believes. Of course, contact is one thing, and communication another. True communication is contingent on having the recipient of the message reply. Perhaps because the show was nearing its end, or maybe because I was a reporter soliciting information, I never heard from most of the artists I e-mailed.

Other artists were disillusioned by the e-mails they did receive -- or lack thereof. Ben Edwards, whose painting was mysteriously moved to the director's office, where it remained behind closed doors for the duration of the show, writes in an e-mail that he was initially thrilled by the idea. After receiving only a few messages from the Hotmail staff, and "other artists pitching this or that," Edwards ultimately came to view the effort as a failure. "So much for the grand vision and great expectations of the Internet as a medium for dialogue and exchange about art," he writes. "I hope the other artists in the show had a better experience with this than I did, but my feeling is that it was a good idea, but in the end people are more interested in seeing the big show than really thinking or talking about it."

It's unrealistic to expect every piece of work to generate a response, yet the e-mail project does seem a refreshingly democratic alternative for a forum for discussion. Of course, an intelligent exchange requires both time and effort to take off; such diligence explains why Rhizome has developed into such a fantastic resource. Yet Rhizome is almost exclusively made up of people immersed in new media. Is this alone the source of their success? Was Huberman's project, which was directed at a much broader range of people, slightly ahead of its time? Or behind it? If the majority of the e-mails were brief and clumsily constructed, does that mean that already, for the few of us hooked into this world, we simply don't appreciate an opportunity to connect with an artist whose work succeeds in making us think?

In 1907, thirty-one years after Bell invented the telephone, Marcel Proust wrote that the phone was "a supernatural instrument before whose miracle we used to stand amazed, and which we now employ without giving it a thought, to summon our tailor or to order an ice cream." These contrary perspectives seem to have been applied to the Net by the New York museums. The Whitney tried too hard to force the Net into its institutional framework, and as a result the museum seemed stodgy and out of touch. P.S. 1, on the other hand, was faithful to the integrity of the medium to the point of fault. Ultimately, the e-mail project expected far too much from those particpating. For the most part, neither artists nor audience seemed particularly interested in the gimmick. Neatly summarizing the results of this gallantly democratic experiment, artist Steven Brower complains, "I didn't realize my art could generate so much verbiage that had nothing to do with my art."

Claire Barliant is a writer living in New York.

![]()

Share your thoughts on Net art

and the artist-audience dynamic in

the Loop.

SPECIAL ISSUE

Street Level FEED's Special Issue on cities THE POSTHUMAN CONDITION ESSAY 06.05.00 06.02.00 DAILIES 06.08.00

|

6.1.100

343.1

David Sheehy: the

internet confessional booth

But those who contacted Lindmann

treated her like their confessor. One man wrote to tell her that her work

changed his life: Before the sauna, he'd been unbearably insecure about

his body. "He would not have written that into the guestbook," Lindmann

insists. "Sending it out into the dark world and knowing that no one's

going to catch it but me -- I think that makes it easier."

I

think this cuts right to the value of the internet in establishing

communication. The piece sounds good, and the context is right for

feedback.

Ben Edwards, on the other hand, gives the experience a

bad rap. The 'failure' of the 'net to deliver dialogue is a lot to hang on

a hotmail account! Maybe he should try some other methods and give it

another shot.

The 'net is a communications tool, and the medium

comes with a certain perspective. However, as with other forums, it is

what the communicants make of it.

I have found newspapers and art

magazines to be quite ineffective at establishing 'dialogue', but they

still churn them out in droves.

The supernatural connotations are a

symptom of our cultural attitude towards technology. It is interesting to

see how personally we take it. We perhaps have become so dependent on

technology as a part of human identity, that when we pin hopes on

technology somehow saving culture, people become very disappointed in it's

failure to deliver.

I'd say the problem today isn't so much with

our communications systems, but with articulating what it is we want to

discuss.

![]()

![]()

The Boston Cyberarts Festival is a biennial exhibition by

artists who use computer technology in their work. Athlantic

Unbound reviews its debut: "The first Boston Cyberarts Festival, which

took place in May, floats atop a longer-running cyberfestival that extends

from Hollywood to Wall Street. Recent entries in the national festival,

not counting the Dow, include the films The Matrix and eXistenz, both of

which take up the theme of digitalization run amok. It's Plato's Cave, the

digital edition, and where, oh where, is the analog sun?" ![]()

![]()

Claire Barliant last wrote for feed about Rtmark's latest stunt, National Phone In Sick Day. " If you

went to work on Monday, you're a sucker: that day, May 1, was National

Phone In Sick Day. Not yet a bank holiday, the event was another of the

activist collective Rtmark's anticorporate pranks, one with a serious

point -- promoting awareness of the deterioration of that increasingly

precious resource, free time." ![]()