Ether 6 Distributed to Centralized

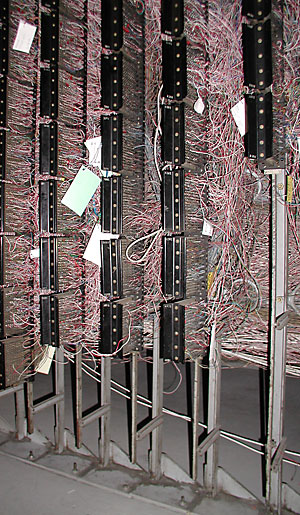

But the model of distributed communications did not make it to ARPANET. Designed as an abstract layer, not as an expensive, separate physical network, ARPANET used existing telephone lines leased from AT&T, lines inevitably based on a centralized model created long ago. In the traditional centralized system used by American telephone companies, long distance lines terminate at a switching station in the oldest and most developed part of a city’s local network, almost always located in downtown. Had a nuclear war taken place, ARPANET would have been completely vulnerable.

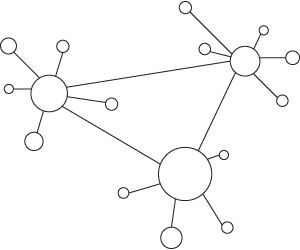

By the early 1970s, peer-to-peer networks such as the Department of Defense Advanced Research Project’s Agency’s ARPANET and the National Science Foundation’s NSFNet proliferated. Eventually these would be linked by a single system called the Internet. NSFNet’s rapid growth during the 1970s made it the dominant entity in the early Internet. The NSF implemented communications between regional networks through a “backbone” leased on lines from AT&T and offered central hubs in each city to which local users would connect. The result was the end of the distributed model.

With the exponential growth and privatization of the Internet and the increasing lack of distinction between data networks and telecom systems, this topology was further centralized. Driven by profit, Internet corporations follow existing systems of networking established by telephony. Interconnections are between major nodes located in city cores. Within cities, fiber optics can be laid down more inexpensively and higher capacity, short-distance networks can be built relatively easily. If, following AT&T’s breakup, there has been a proliferation of long-distance carriers, these have to access the local central office for distribution. Naturally, this centralizes the network, privileges the bigger players, and increases the divide between a digital hub in the city core and the digital desert beyond.