|

Virtual

Urban

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

My mother grew up in Brooklyn - a beautiful tree-lined neighbourhood near a park that emptied into Sheepshead Bay. She had sidewalks and always dreamed of living where there were none. So eventually she moved to Poughkeepsie, New York, and lived in a green suburban neighbourhood that used to be a farm and had no sidewalks. When I was growing up on this transformed farm, I dreamed of living in a place that had sidewalks. Sidewalks where I could ride my bike and walk in between the street (where as a child you were not supposed to play) and the neighbour's property (where as private property, you were not supposed to trespass). Someone's mother or father would yell at you through an open window getting you in trouble for cutting through their lawn. I dreamed of skipping on sidewalks playing games with the cracks in the concrete. I read in an essay that in Albania, the sidewalks and roads look like they've been walked upon by a dinosaur. I'm going to Albania. I'm going to Albania next week to monitor their local elections through OSCE (Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe) and ODIHR (Organisation for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights). I have no idea where I will be deployed. It could be a city with sidewalks. It could be a village without them. I won't know until the day I arrive.

I've never been to Albania. Before this assignment, I knew the usual stories about the country, its isolation and its anarchy. In 1987, I sailed along the coastline on a Greek ferryboat travelling from Dubrovnik to Corfu. I remember a mixture of fear and curiosity about this totalitarian, isolated nation. From the deck, I swore I could see the infamous concrete bunkers of Enver Hoxha's paranoia. Swimming in my head were National Geographic-like images of horse drawn wagons and peasants; a folkloric myth of another century that existed still today.

Then there were changes in government and political borders. Wars and refugees - greed and guns - economic disasters. In an Indiana University alumni newsletter, my friends from MBA School listed me as missing in action and possibly responsible for the pyramid schemes in Albania. Many Albanians, in the hope of quick prosperity, lost their meagre life's earnings and learned a first lesson in capitalist freedom. There were more wars, more guns, and more refugees. Economic desperation grew and the magazine images that influenced my once romantic, mythical view, now showed the Italian-bound ships full of asylum seekers. The texts described women being sold for prostitution and others who had been fooled by smugglers. The horror stories accompanied photographs of dark, brown vacant eyes and hollowed faces.

The night before I depart

for Albania, I sit in café on an artificially created Main Street that

represents the new concept in shopping malls, trying to give Generica

a cosy, small town America feeling. I drink a $3.97 (with tax) cappuccino

composed of 4/5ths steamed milk resembling shaving cream and conjure

an image in my head of Albania. When I think of Albania, I imagine a

whirlwind of dust and shades of brown and grey, reflected in an afternoon

light. A poor, but chaotic, vibrant atmosphere amidst the concrete blocks

that are the sad coincidence of new discoveries in the use of concrete,

70s urban grandeur, and Communism. My vision of Tirana is more passionate

and wild than the Albanian towns of Macedonia I visited or the spice

and mystery of Sarajevo. Reading about the country's long history and

my virtual tours on the Internet provide a deeper dimension and satisfy

my knowledge that Albania is more multi-faceted than the television

or magazine images.

Transition countries are like sidewalks with cracks and holes. They are the space in between - not rich from capitalist democracy and no longer hard line Communist.

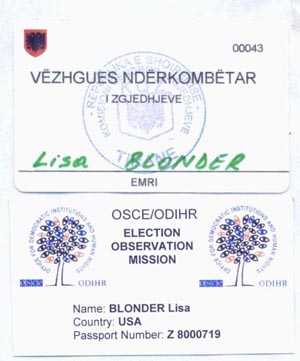

I leave for Albania as an "official" observer - not a regular tourist. I hear that there are some security restrictions and that I will be matched with a non-American and local interpreter for the task of observing the voting process. I imagine a new picture. This warm-blooded nation, teeming with all kinds of passion, a passion that too often than not gets out of hand. And I picture us - the mission; the invaders of this space even if diplomatically welcomed. We represent the cold icy breeze. A freezing slap of frosty billowing steam that wakes you up as you open a freezer door on a hot summer day. We are the voice of reason - rational thought - civilisation and all that it represents. The US organiser rattles on to me one day about democracy, the day the bureau has been renamed the Harry S Truman Department of State. Between artificial Main Street and the Internet picture of Skenderbeg Square, I sit in the space in between. 27 September, I arrive in Albania and the first images are those of the past. Driving in from the airport, the infamous bunkers of Enver Hoxha dot the countryside. Everywhere, in lines, at street corners, in fields, in cow pastures, in a back yard, they sprout like mushrooms after a rain. "During former times" [for some reason this is an endearing phrase to me that mentally sends me back to a seemingly pre-historic setting prefacing an (un)intentionally humorous story of absurdity from real life under Communism]. During former times, to test the strength of the bunkers, a soldier would sit inside one and the military would attempt to shell it to pieces. The bunkers were quite strong and the soldier would usually emerge after the 15 minute period most likely shaking and deaf, but alive. Or so the story goes… in Albania you can never tell what is truth and what is myth. The bunkers, as if soldiers themselves, were strong enough to ward off the enemies of the state - the Americans and Westerns. The very same who now photograph them like tourist sites and poke around trying to comprehend their social significance. I was told that a Czech filmmaker made a movie about the Albanian bunkers. We tried to find a copy on videotape, but the sellers' said that it isn't even in the movie theatres yet. Sokol, our interpreter and a dynamic young man of 25, swore he had seen the video for sale while studying in Budapest for his Masters in Political Science. Our driver is a tax policeman and entrepreneur who does great imitations of Berisha, the Democratic Party leader. He actually won a national prize for his imitations. Things are never as you may imagine.

I asked the Albanians with us, what was and what is now their relationship with these stone and metal mushrooms that dot their country. They essentially said that life just existed and continues to just exist around them. They make good shelters, storage areas, and bathrooms. A few converted larger bunkers into bars or kiosks. Some try dig them up to make way for farmland, which proves to be a difficult task since their strength fought off invaders for so long. The metal domes are dissembled and smelted for income. Albanians seem to have a way of turning the worst of a situation into a humorous, but poignant anecdote. I bought a bunker ashtray made of stone at a local souvenir shop - the dome comes off so that you can empty the ashes. The other observers all wanted one after I showed it to them.

I find it always interesting how people transformed former icons of a regime into the present. In Albania, street names were changed and statues of Hoxha were torn down. The bunkers take on new, more practical purposes. The mausoleum of the dictator was turned into an International Centre of Culture. The planned Communist headquarters is now a top hotel in Tirana.

In a country where until recently the primary mode of transportation has been the wagon drawn by horse or donkey, the people have taken to the roads in hodgepodge creations made from a Frankenstein mixture of automobile parts or in fancy cars legally or illegally imported from abroad. There are many Italian and German license plates. Although many walk long distances without a thought, people now love to drive and will hop in the car just to venture a short distance despite the lurking fear of having this valuable asset stolen every time it is parked. During our drive to the coast, we passed numerous automobile graveyards. Along one side road, the multi-coloured doors were lined up like dominoes. In Tirana, I made up a new game - Crossing the Street. It was like trying to pass between bumper cars at an amusement park. I never knew if the drivers would stop or if they would just continue, hit me and bounce off another car. Traffic lights mean little or nothing - few drivers actually pay attention to them. In the square, there is no attempt to yield to either a pedestrian or another vehicle. I was an amazon chicken crossing the road.

It all makes me think of another world called Washington, DC, where on Dupont Circle, the traffic flows under park with its fountain and benches. The traffic circle encompassing it along with its arteries have about a dozen traffic signals, which actually stop cars when the lights turn red.

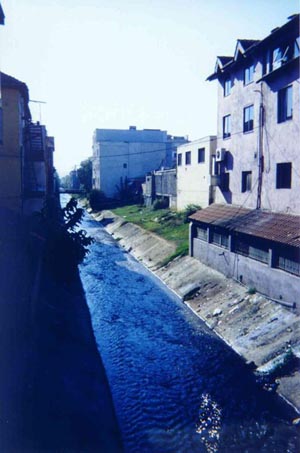

In Albania over the last ten years, there has been a boom of construction. Most of it illegal. In the city parks, entrepreneurs built kiosks, restaurants, bars, pool halls, and cafés hidden under the canopy of green trees. Illegal buildings and stores also line the garbage-filled canals that divide the city.

I manage to find a relatively empty café for a coffee - the first real coffee I've had since returning to the US, where it just doesn't exist. To me, this Albanian machiatto tastes like heaven. Cafés provide a lively atmosphere for people, mostly young men to gather, drink coffee and raki, eat, and talk. Home-made raki comes disguised in Glina bottles, so you have to always check if you are having a sip of mineral water or potent raki. Thirsty in the middle of the night, I stumbled for the water bottle next to my bed and almost gulped down a mouthful of raki instead. Oops wrong bottle!

So many men everywhere - young men, really old men. Those who are not relaxing in cafés set up their cardboard box or wooden table to sell everything from Snickers chocolate bars to an American dream in the form of applications for the green card lottery. Many shine shoes, grill corncobs or chestnuts, while others offer to tell you how much you weigh. In one corner of Skenderbeg Square, moneychangers openly wave large wads of worn, but colourful LEK to attract potential customers. It's a man's world. These are the main streets of Tirana. There are also the police guarding the ministries with their Kalashnikovs, finger on the trigger. The more relaxed uniforms are guarding polling stations. Snipers perch on the rooftops preparing for any trouble at the various political rallies held in the main square or following the outcomes of the elections. On the roads, men in black ski masks, Special Forces, look for potential troublemakers. Our interpreter and driver were stopped one evening, but quickly let go without a worry when they eyed the OSCE/ODIHR sign.

There has been a recent and rather successful crack down on illegal construction in Tirana. However, as a result, a high-level government official in the Ministry of Planning was murdered for refusing to take bribes and for initiating the demolition of the illegally constructed kiosks. Parks are now returning to their original purposes and the streets are less crowded with the ugly metal constructions.

Ironically, one vast vacant lot between the Tirana International Hotel and the market has been vacant since 1991, a vivid reminder of the impact of the Albanian pyramid schemes. Hajdin Sejdija, a Kosovar from Switzerland, began a series of investment projects through the Swiss-Albanian Illyrian Bank, which promised investors rich returns from the construction of a Sheraton Hotel complex. The foundations were dug, but later abandoned to the weeds and garbage as the schemers ran away with the cash. "Sejdija's Hole" remains empty, home only to some Roma gypsies. Sejdija sits in a Swiss jail.

This is the setting in which we will conduct our observations: in a former Communist country that has been thrown into the West and as a result, possesses this odd mixture of what doesn't work and what tries to work. A combination of what is new and what is old [like religion], but in fact is now also new since so much was disallowed under Hoxha's totalitarian Communist regime.

As I walk down the main boulevard, I detect the distinct scent of Windex [an ammonia window cleaner] in the air and notice that in this dusty town, the windows are clear and are often polished by their shop owners. Towards the end of the broken, smashed sidewalk, new apartment blocks are being constructed and the scent becomes stronger changing into the heavier scent of fresh paint. Back at the hotel, from the terrace restaurant I look down upon Skenderbeg Square as we meet with some other OSCE/ODIHR teams from Tirana. An apartment house nearby shows off various satellite dishes, but very few water collectors that permit the inhabitants to have running water. My OSCE partner, a Brit married to an Albanian woman, told me how although his wife could afford to install the tank went for years without this basic luxury. In a highly polarised political environment, the Vote as a Socialist and live as a Democrat billboard "clarifies" the political and general situation even further. Although these are only local elections, they will be a barometer for the national elections next June and will test the strength of "democracy" in the country. By this, I mean: Will there be violence or intimidation? With either major party create problems to the point of diluting the overall integrity of the elections? Will the Berisha faction of the opposition Democratic Party (DP), known to stir violence and reject reforms, adhere to the results if they lose? Will they boycott?

Work begins. Various officials brief us about the general Albanian political and security situations, procedures, and our obligations. The mission is comprised of 251 observers from 26 nations. We are young and old and include job seekers like myself, pensioners, election officials, current and retired Foreign Service officers, academics, and even an underwater archaeologist from Luxembourg. For some it is a holiday. Others take it more seriously and are committed to the ideals and responsibilities of the mission. Human dynamics are fascinating. Over 900 polling stations out of approximately 4.000 around Albania will be observed.

I am based in Tirana where there will be four elections instead of two as elsewhere: City Mayor and Council, District Mayor and Council. My OSCE partner and I plan out our route for Election Day, making sure that the polling stations are where they have been designated. In our Zone 8 of Tirana, the members of the Local Elections Commission have had a few disagreements over the locations of the polling stations. The stations in our sections are located in schools, privately owned café bars, a fruit warehouse. The commission eventually resolved the location issues the next day - Election Day that is. The polls open at 7:00 in the morning. A final decision by a higher body puts the polling stations back in the originally designated sites - a nearly dilapidated kindergarten and small bar, supposedly outside of Zone 8. The first opened at 10:30 and the other at 12:30. Forty percent (40%) of the polling stations observed around the country didn't open on time. In Zone 8, it is essentially a petty, deliberate quarrel between the Socialist (SP) and Democratic (DP) parties to cause delays, plant the seeds of distrust, and generally give each side grounds to protest the outcomes of the elections. We enter as observers, but often become the sounding board for each side of the story, like parents caught between two children fighting over a bicycle. When you make reference to ODIHR - the organisation which we represent - it sounds like you are saying "Oh Dear!" which is how I felt at times.

Our duty is to observe the opening, the polling, and the closing and counting of one polling area and report about the polling process including any problems or incidents of intimidation or inappropriate influence. We are not there to assist in the process. So when a polling station doesn't open until 12:30, all we can do is sit in a café next door and wait for something to happen. After living outside my home country of the US for so long, people get an impression that I do not like America. One of the things that I have learned to appreciate about my homeland is our idea of democracy. I've been asking a lot of people over the last few months about what democracy means to them. To me, it is primarily about having the freedom and institutional mechanisms to voice my opinion. I've learned that to others it means something completely different. While watching the Albanians vote, I was in awe of them individually and in how far they have come as a nation and as a society. We sometimes underestimate the power of regular people. The first people I observed at the polls were an elderly couple; she dressed with a white babushka kerchief around her head, woollen stockings and grey skirt, he in a faded grey suit and a gentleman's hat. They were illiterate and their son helped them fill out the forms. He was an attractive young man, tall blonde and blue eyes with a serious look on his face. The elderly man held up his inked black thumb in pride after he slipped his coloured ballots into the designated boxes. Many families voted together. It wasn't a pure matter of patriarchal influence over the others, but more about the culture of Albania. Some of the polling stations had a festive atmosphere, especially in the countryside from what I heard from the other observers. Polling station in School No. 19 was like a surreal Camelot with citizens voting under the whimsical decorum of a kindergarten classroom full of children's decorations and finger paintings.

We stay up until about 1:00 in the morning observing the count of the ballots, but quit since only two boxes had been counted by this time and the Local Elections Commission seemed to have everything under control. The next day, the OSCE/ODIHR commission and Council of Europe issue their joint statement to the press: "These elections were held, in contrast with previous occasions, in a tense but remarkably peaceful atmosphere with only a few isolated incidents of violence [which] was a reflection of restraint exercised by political parties and important measures undertaken by the Government to improve public order. Some irregularities [errors and omissions in the new voter registries, missing of deadlines, inconsistencies in transitional provisions in the election code introduced by Parliament, independence of the Central Election Commission (CEC)] were noted, but none seemed significant enough to impact the outcome. These elections took place under a reformed constitutional, legislative, and administrative framework…[and] in general provided a sound basis for democratic elections." Our job was over.

We, the American group, land in Vienna, Austria for a short layover before returning to the US. All of us are disoriented by the orderly cleanliness of the city as we board the metro for Vienna's famous Ferris wheel and a different perspective of the city. Tirana and Vienna would probably be at two opposite ends of an urban spectrum. I had never had a burning desire to come to Vienna, but fell in love with the place during my evening and early morning walks that occupied the less than 24 hours layover. The city is like a cake full of rich layers all elaborately decorated with coloured frostings. I learned something very interesting, at least to me, from a shop window during my morning walk - that petit point needlework originated in the Hapsburg dynasty. It reminds me of the night table next to my mother's bed, full of small purses from my grandmothers and great-grandmothers. All petit point.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|